In this post, we shall illustrate the intuitive meaning of the Laplacian of a multivariable function as a measure of the concavity of the graph of the function, where this concavity is itself measured via average values in local neighbourhoods.

- The Laplacian

- A Hint at the Answer

- Measuring Concavity Via Average Values

- The Intuitive Meaning of the Laplacian

- The Intuitive Meaning of the Laplace, Poisson, Heat and Wave Equations

The Laplacian

Let be some smooth1 multivariable function. To each such

, there is associated it’s Laplacian

, defined by

The purpose of this note is to illustrate the intuitive meaning of the Laplacian.2

A Hint at the Answer

We note that the Laplacian is exactly the divergence of the gradient of

. Given a vector field on

and

, we know that if the vectors at neighbouring points point outward away from

, than the divergence of the field at

is positive, whereas if they all point inward toward

the divergence is positive, and more generally the numerical value of the divergence captures exactly the balance of inward and outward pointing neighbouring vectors.3

In the case of the gradient of , what does it mean if neighbouring vectors point outward? Recalling that the gradient points in the direction of steepest ascent (along the graph of

), we see that in such a case the graph of

at

must be concave up. Conversely, if the neighbouring vectors point inward, the graph of

at

must be concave down.

This leads us to think that is a measure of the concavity of the graph of

at

. In fact, when

,

is just the ordinary second derivative, and it is of course well-known that the ordinary second derivative is a measure of the concavity of the graph. Thus we suspect that, in this particular sense, the Laplacian is the natural extension of the ordinary second derivative of single variable functions to multivariable functions.

Measuring Concavity Via Average Values

Consider the ordinary second derivative of a single variable function. In what sense exactly is this second derivative a measure of the concavity of the graph of the function? As it is the rate of change of the first derivative, using the interpretation of the first derivative as the slope of the graph, it is clear that a positive second derivative means upward concavity and a negative second derivative means downward concavity. Moreover, the rate of change of the slope clearly correlates with the degree of concavity.

In place of the rate of change of the slope, we can measure the degree of the concavity in a different way, by looking at local average values. At a given point , consider the values of the function at neighbouring points. Certainly, in the case of upward concavity, neighbouring values are larger than

, the value at

, and, in the case of downward concavity, the neighbouring values are lower than

. Moreover, for sufficiently small neighbourhoods, in the case of upward concavity, the degree of concavity correlates with the rate at which the average neighbouring value rises above

with the size of the neighbourhood (and a similar statement holds for downward concavity). In the case of mixed concavity, such as saddle points, there is a mixture of neighbouring values above and below

, and these make opposing contributions to the average deviation from

. We are thus led to consider average values in local neighbourhoods of

.

Let us consider an example.

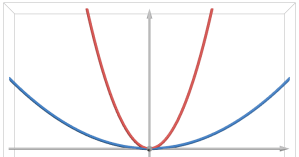

In Figure 3 are depicted the circles described by for various values of

. One can see that, as

increases, the concavity at the origin decreases. Moreover, a simple calculation shows that

. Thus the second derivative, the one-dimensional Laplacian, is proportional to the concavity. Next, consider the values at the neighbouring points

and

, for small

, and form their average; this average is

. We are interested in how this average behaves as

changes. Near zero, we have that

Thus, we see that, in sufficiently small neighbourhoods, the rate at which the average value rises with is (up to the constant

) exactly the value

of the Laplacian.

We can generalize the analysis in the above example as follows. For an arbitrary smooth function and a point

, consider the average of the two values at

and

. This average is given by

This is clearly smooth in , and, moreover, easy calculations demonstrate that

Thus, by Taylor’s expansion, we have that

This yields an interpretation of the Laplacian as a measure of the rate at which the average value deviates from as we expand the region over which the average is taken. This is a specific sense in which the second derivative, the one-dimensional Laplacian, captures the concavity of the graph.

In the above analysis, we considered averages of values at points near . Specifically, we considered the average of the values on the set

. This is the zero-dimensional spherical boundary of the neighbouring interval

, a one-dimensional ball, and it is just as natural, if not more natural, to consider the average instead over this interval. At

, the average value of

on

is

Our goal here is to demonstrate a connection between these average values and the Laplacian

. As before, we thus investigate the local behaviour of

at

. At

, the above expression is ill-defined and instead the average value

is of course set to be

; an easy application of L’Hopital’s rule shows that

is then continuous. In fact, we can show that

is smooth (this is non-obvious only at

). To see this, set

. By the fundamental theorem of calculus,

is smooth. For any

, by Taylor’s theorem, using the integral form of the remainder, we have that

We can identify the derivatives of : first, it is clear that

and, by the fundamental theorem of calculus,

, from which it follows that

. In fact, a simple induction shows that

vanishes for even

and

for odd

. Consider the case

. We get that

Using the substitution , we can rewrite the integral remainder term and get

Now, noting that , we find that

The smoothness of now follows from the Leibniz integral rule combined with the fact that

defines a smooth function on

.

Let us now return to investigating the local behaviour of at

. The above expression can be used to compute

. However, having established the smoothness of

, we can compute this derivative more simply as follows. By the quotient rule and the fundamental theorem of calculus, for non-zero

, we have that

Using smoothness of (and the consequent smoothness of

), we see that

where in the second line we have used L’Hopital’s rule. In a similar manner, we can also compute the second derivative . For non-zero

, we have that

Using smoothness of , we see that

where, again, in the second line we have used L’Hopital’s rule. The Laplacian of at

has made an appearance. Using Taylor’s theorem for

, we may now write the following local expression

As suspected, (for sufficiently small neighbourhoods, and up to a constant) the second derivative at

controls the rate at which the average value deviates from

as we expand the neighbourhood.

In the case of a one-dimensional domain, we have now considered averages over spheres and balls. There is yet another form of average of nearby values which we can link to the ordinary second derivative, the one-dimensional Laplacian. The ordinary second derivative can be expressed as the limit

(One can easily check that the limit above does indeed coincide with the second derivative using L’Hopital’s rule.) From this, it follows that, as

This simply recovers the result above in the case of an average over a neighboring sphere. In this case, however, we interpret the lefthand side as the average of neighbouring values along the positive and negative axial directions, and denote by . We do so because we can perform an analogous analysis in higher dimensions. For example, consider the case of two dimensions. In this case, the Laplacian

is the sum

and can be expressed as the limit

(Once again, one can easily check that the limit above does indeed coincide with the Laplacian using L’Hopital’s rule.) From this, it follows that, as

Again, the lefthand side is the average of neighbouring values along the axial directions, and the result tells us that (for sufficiently small distances to , and up to a constant) the Laplacian at

controls the rate at which this average value deviates from

as we expand the neighbourhood.

A final remark for this section: note that in every local expression, there was no linear term in . This makes sense because each averaging function is clearly an even function of

.

The Intuitive Meaning of the Laplacian

In one dimension, the prior section provides a satisfying answer to the question of the intuitive meaning of the Laplacian. In fact, this interpretation holds true in all dimensions. The specific result, for smooth , is that

For a proof of the first two, see The Laplacian and Mean and Extreme Values by Jeffrey S. Ovall (The American Mathematical Monthly, vol. 123, pp. 287-291 (2016)). As for the third, it follows from the identity

where denote the standard basis vectors of

. Note that, in the case

, these reduce to the local expressions which we derived in the prior section (except that the remainder term is given the stronger expression

instead of

).

In fact, in the same aforementioned paper, higher order approximations are provided, from which one can easily derive the well-known fact that, if, for a given , the Laplacian

is zero in some open region

, then the value of

at any point in

is exactly equal to average of

over any ball

or the boundary sphere

, where

, centred at that point.

The Intuitive Meaning of the Laplace, Poisson, Heat and Wave Equations

We have now completely answered the question of the intuitive meaning of the Laplacian. It is natural now to consider the intuitive meaning of differential equations in which the Laplacian appears. Let us consider the Laplace, Poisson, Heat and Wave equations. We can gain an intuition for these based on the physical contexts in which they arise.

The Laplace and Poisson Equations. Let us begin with the Laplace and Poisson equations. For a scalar field , these are the equations

and

, respectively, where

is some specified function. For example, if

denotes the mass density in three-dimensional space, the corresponding gravitational potential

satisfies

The corresponding gravitational force is given by , and so a particle is always pushed in the direction of decreasing potential

, with a force magnitude proportional to the rate of decrease; in particular, near any given point in space

, a particle is pushed toward or away from

depending on whether or not this increases or decreases

. Here, whether or not there is an increase or decrease can be assessed by measuring the deviation of the average of the nearby values from the potential

at

, which, as we have seen, is exactly what is measured by the value of the Laplacian

. The above equation says that the Laplacian is proportional to the mass density, and so it says that particles are pulled toward regions of positive mass density, with a force magnitude which is proportional to the mass in the region.

In the case where the mass density is identically zero, the potential

satisfies Laplace’s equation

. This equation says that, at any point

, the value of the potential at

is exactly equal to the average of the neighbouring values. Thus, at any point

, a particle is not compelled to move in any direction (it is in an equilibrium state), and we get a zero gravitational field, as expected from the zero mass density. \\

One can make very similar interpretations for the equation for the electrostatic potential

.

The Heat Equation. Next, let us consider the heat equation. This is the equation

where represents temperature at a given point at a given time and

is some non-negative constant. At a given time

, the righthand side may be written as

. The equation determines the evolution of the temperature throughout space over time, which is to say the flow or diffusion of heat throughout space. At any given time

, and spatial point

, the value of

at $\mathbf{p}$ represents the deviation of the average of the neighbouring temperature values from the temperature at

at time

. Thus, the equation says that the rate of change of the temperature at

at

is proportional to this difference between surrounding temperatures and the temperature at

. This is intuitive and aligns with Newton’s law of cooling. The non-negative constant

then represents the ease with which heat flows through the medium and so is referred to as the thermal diffusivity of the medium.

The Wave Equation. Finally, let us consider the wave equation. This is the equation

where represents the size of a wave disturbance at a given point at a given time and

is a non-negative constant. At a given time

, the righthand side may be written as

. The equation determines the propagation of the wave throughout space over time. At any given time

, and spatial point

, the value of

at

represents the deviation of the average of the neighbouring disturbances from the disturbance at

at time

. Thus, the equation says that the acceleration of the point

, due to the wave, is proportional to the difference between the surrounding disturbances and the disturbance at

. This is similar to simple harmonic motion where the acceleration of a particle is proportional to its distance from an equilibrium point, except that here the equilibrium is the current state of the

and the acceleration takes into account the disturbance not only at

but at points nearby

. The non-negative constant

then represents the ease with which the disturbances at points nearby to

impact the disturbance at

itself, from which it is not too difficult to guess that

turns out to correspond to the speed of the wave.

- We can consider the Laplacian, and all other related material here, for, e.g.,

functions. For the purposes of this note, however, the degree of smoothness is a distraction, and so we consider only smooth, that is,

, functions. ↩︎

- The Laplacian, and all other related material here, can of course be considered for functions which are defined only on subsets of $\mathbb{R}^d$. The considerations carry over easily, and so domain considerations are a distraction, and so we restrict to functions defined on all of $\mathbb{R}^d$. ↩︎

- Throughout, vectors will be denoted in boldface. ↩︎